Gun activists frequently misquote and misattribute words to the founding fathers. The founding fathers? idea of The Right To Bear Arms was framed much differently than today?s debate.

There?s a quote floating around the internet, attributed to George Washington in his first State of the Union Address, which says

Firearms stand next in importance to the constitution itself. They are the American people?s liberty teeth and keystone under independence ? from the hour the Pilgrims landed to the present day, events, occurences and tendencies prove that to ensure peace security and happiness, the rifle and pistol are equally indispensable ? the very atmosphere of firearms anywhere restrains evil interference ? they deserve a place of honor with all that?s good.

As stirring as that quote is to some people, George Washington never wrote or said that, nor did he say anything to that effect. The likely source of that quote is an article from a 1926 issue of a magazine called Hunter-Trapper-Trader attributed to C.S. Wheatley.

George Washington is hardly the only founding father being falsely quoted like this; a Google search is all it takes to discover that the majority of pro-gun quotes commonly attributed to the founding fathers are fakes, or are taken out of context. Thomas Jefferson never wrote ?the strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort, to protect themselves against tyranny in government;? these words were first printed by the Orlando Sentinel in the late 1980s.

Jefferson also did not say ?the beauty of the second amendment is that it will not be needed until someone tries to take it;? this quote seems to be from a fictional Jefferson in an independently-published novel called On A Hill They Call Capital (sic.)

John Adams, who was famously suspicious of unrest among common people, would never have declared ?arms in the hands of the citizens may be used at individual discretion for the defense of the country, the overthrow of tyranny or private self defense,? and Alexander Hamilton could never have said ?the best we can help for concerning the people at large is that they be properly armed? in the 184th Federalist Paper, as is claimed on a prominent pro-gun website, because there were only 85 Federalist Papers.

Fake quotes like these are abundant and they?re not confined to fringe message boards or bumper stickers. They are widespread and they?ve found their way to the top of the pro-gun mainstream.

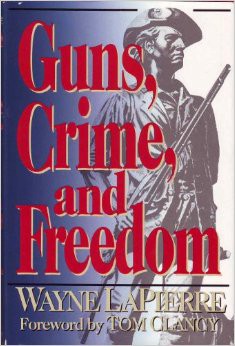

In the first chapter of his book Guns, Crime & Freedom, Wayne LaPierre, the executive vice president and public face of the National Rifle Association, argued that virtually every important figure in early American history believed that the population should be armed in the manner that the NRA currently endorses.

This stern-looking patriot compels you!

This stern-looking patriot compels you!

In support of his argument, LaPierre misquoted James Madison, cited a deleted sentence from the second draft of the Virginia Bill Of Rights as if it were in the actual Virginia Bill of Rights, and took famous non-gun-related quotes from John Adams and Benjamin Franklin out of context to make it seem like they?d support today?s NRA. This is not some independent printout being sold at a gun rally or an email chain letter; this book is a published, highly-regarded source for people arguing in favor of the NRA?s position on gun control ? complete with a foreword by Tom Clancy ? and it?s riddled with inaccuracies and fake quotes.

People invoke ?the founding fathers? in toto pretty often here in the US, and this is a dubious tactic for a number of reasons. For one: The founding fathers were deeply flawed by today?s standards; the United States of America as envisioned in the original constitution is an agrarian, slave-holding nation where only land-owning white Protestant men have the right to vote or hold office. To invoke ?the founding fathers? at all is to invoke men whose words have been amended and reinterpreted many times in order to fit the evolution of American society.

These early American statesmen disagreed with each other quite a bit.

These early American statesmen disagreed with each other quite a bit.

The founding fathers were also a group of men who disagreed with one another on pretty much every conceivable topic; claiming that ?the founding fathers? felt a singular way about a specific idea is like claiming ?all sports fans? unanimously consider Peyton Manning the all-time best Quarterback.

And our record of what the founding fathers said is incomplete: some constitutional debates were transcribed but others were not, and we have a thick record of the speeches and writings by some founding fathers but not others.

So any claim that ?the founding fathers? would have collectively felt one way or another about one of today?s political issues is probably not true; at the very least, this type of claim is not provable.

But despite how tenuous it is to invoke the founding fathers when arguing a point, it is absolutely true that the founding fathers ? and more specifically their intents ? are at the core of the issue of guns in this country. This ?right to keep and bear arms? was their idea; no other modern Western nation has a similar right placed in its constitution. Because of this, fully understanding the founders? intent regarding the second amendment is the key to dissecting and discussing the issue of guns in American society.

During colonial times, each colony relied on an armed citizenry to defend against aggression from Native Americans and the French. Men were generally required to own at least one firearm for this purpose and to have a firearm on their person at all times; in some places this included a mandate that guns be brought everywhere, including to church. When an organized fighting force was needed, each colony had its own militia made up of part-time citizen-soldiers that were called to action and disbanded as needed, and this militia was usually supported by private citizens carrying their own weapons. This tradition continued into the American Revolution, where the new, centralized Continental Army was heavily supplemented by local and state militias armed with privately-owned weapons. There were also no police forces in colonial times; policing was largely done by elected sheriffs and the local militia.

What became our second amendment is the result of the new nation deciding on the best way to defend itself now that the colonies had become the United States.

For the most part, it is clear that many of our nation?s founders approved of this part-time militia system, and deeply feared the idea of a centralized standing army. James Madison, at the Constitutional Convention, said:

The means of defence against foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war, whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people.

Elbridge Gerry, a congressman from Massachusetts and Madison?s future vice president, echoed this sentiment:

What, sir, is the use of a militia? It is to prevent the establishment of a standing army, the bane of liberty?Whenever government mean to invade the rights and liberties of the people, they always attempt to destroy the militia, in order to raise an army upon their ruins.

Alexander Hamilton also believed in defense by militia, but he believed that the militia should be regulated and directed by the Federal government. In the Federalist ? 29 he wrote:

It requires no skill in the science of war to discern that uniformity in the organization and discipline of the militia would be attended with the most beneficial effects, whenever they were called into service for the public defense. It would enable them to discharge the duties of the camp and of the field with mutual intelligence and concert an advantage of peculiar moment in the operations of an army; and it would fit them much sooner to acquire the degree of proficiency in military functions which would be essential to their usefulness. This desirable uniformity can only be accomplished by confiding the regulation of the militia to the direction of the national authority.

And Robert Yates, an Anti-Federalist, appears to have been as skeptical of the militia as he was of an army:

What, would you use military force to compel the observance of a social compact? It is destructive to the rights of the people. Do you expect the militia will do it, or do you mean a standing army? The first will never, on such an occasion, exert any power; and the latter may turn its arms against the government which employs them.

This debate over the merits of a standing army and the militia appears to be the primary concern surrounding the drafting of the 2nd amendment. Several drafts of what became the second amendment include clauses to the effect of ?a standing army of regular troops in time of peace, is dangerous to public liberty, and such shall not be raised or kept up in time of peace but from necessity,? but this was eventually dropped by majority vote.

What we are left with is this:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

This is a very confusing sentence on the surface; it appears as broken English, and the second two sentence fragments can reasonably be seen as a non-sequitur to the first two. But it is clear after searching through The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 that the term ?Arms? was firmly limited to the heavily debated topic of national defense. ?People,? in this context, refers to the Nation itself when acting in its own self-defense, and the ?right to bear arms? was treated as a collective right. It?s saying The Nation can not allow itself to be disarmed, because the Nation needs to defend itself. Private gun ownership among certain people was assumed due the circumstances of the time, but the constitutional right to bear and shoot those guns is firmly and explicitly confined to the defense of the Nation.

The Second Amendment cannot be interpreted properly without understanding this context. Contemporary gun enthusiasts may argue against this interpretation of the 2nd Amendment, but this is the way the 2nd Amendment was interpreted by the courts for almost two hundred years, without much controversy, and the majority of scholars and experts still believe it is the correct way to read it today.

It is difficult to determine what the founders thought we should do with private guns during peacetime, or what they might think of gun rights now that we have a standing army. Nowhere in the recorded constitutional debates, nor in the drafts of the 2nd amendment, did a founding father advocate for ? or even discuss ? the common people?s right to bear arms at their own will. Because of this, anyone who claims the ?Founding Fathers? felt one way or another about this is lying. There?s simply no evidence to make a claim one way or another.

They certainly discussed many other issues related to defense: If you read the transcripts from the Constitutional Congress, you?ll find a fairly impassioned debate regarding the rights of pacifists in wartime, another debate regarding the quartering of troops in private residences, and a brief discussion regarding whether or not it was even possible to defend the wide Eastern shore from an invasion. But despite there being hundreds of founding fathers, dozens of whom have extensive records that we can search through and read, I can find only one ? Samuel Adams ? who consistently and provably had a fixed opinion that echoes the current views of the National Rifle Association and other contemporary gun-rights activists. One out of hundreds is the opposite of unanimous. So, it?s categorically wrong to say the ?Founding Fathers? believed that common people should be able to carry their guns around and do whatever they want with them. At the very least, that type of argument is completely unprovable.

Remember: the ?Founding Fathers? seem to have been largely distrustful of common people. Their world was a slave-owning one where only land-owning Protestant white men ? at most 6% of the population ? were thought worthy to vote at all. Even with this amount of restriction they still decided that the election of president and senators should happen behind closed doors by only the most elite of that elite group of people. Today we have universal suffrage and we directly elect our senators, but primary elections are a recent invention, and we still have the electoral college, which has overruled the popular vote more than once, so it?s safe to say that the framers? distrust of the average person lives on even to this day. It seems unlikely to me that people who were this dismissive of the Average Joe would also be in favor of an openly-armed civilian population. But this would not be provable, either.