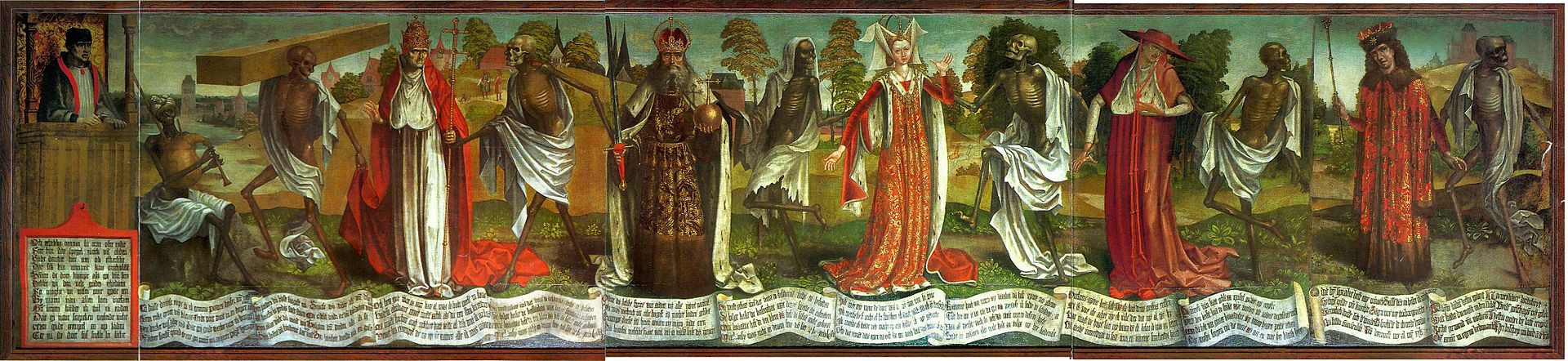

Danse Macabre by Bernt Notke (c.1440-c.1509), located in St Nicholas? Church, Tallinn

Danse Macabre by Bernt Notke (c.1440-c.1509), located in St Nicholas? Church, Tallinn

?The mortality in Siena began in May. It was a cruel and horrible thing. . . . It seemed that almost everyone became stupefied seeing the pain. It is impossible for the human tongue to recount the awful truth. Indeed, one who did not see such horribleness can be called blessed. The victims died almost immediately. They would swell beneath the armpits and in the groin, and fall over while talking. Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another; for this illness seemed to strike through breath and sight. And so they died. None could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship. Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could, without priest, without divine offices. In many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. I, Agnolo di Tura . . . buried my five children with my own hands. . . . And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.? -Agnolo di Tura (chronicler from Siena, 14th century)

The Great Mortality (or Black Death as it is now known) was a watershed event in the history of Europe and the world. Between 1347 and 1351, the plague killed about 75 million people and up to 50 percent of the population.

people in Tournai, in present-day Belgium, burying the death (c.1353 illumination)

people in Tournai, in present-day Belgium, burying the death (c.1353 illumination)

The Black Death was a great equalizer, to a certain extent, in that neither rich nor poor were safe from the pestilence. While the rich nobles had the advantage of great mobility, they had no greater immunity if the disease arrived. The notion of the plague as a great equalizer is very much present in the surviving artistic responses.

Giovanni Boccaccio and Francesco Petrarch mentioned the devastation of the Great Mortality, with the former using it as a backdrop in his famous Decameron. Among the visual arts, a popular theme was the danse macabre. Danse macabre (dance of death in French) refers to a style of paintings and woodcuts created in the aftermath of the Black Death (and into the Renaissance) depicting dancing skeletons taking people to their graves.

Bernt Notke?s Danse Macabre in Tallinn

Bernt Notke?s Danse Macabre in Tallinn

Bernt Notke was a German painter of the Gothic style who was active in the Baltic region during the latter half of the fifteenth century. His Danse Macabre, currently in Tallinn, remains one of the finest surviving examples of danse macabre painting from the late Medieval period. From the pope on down, different ranks in society are being shown taken by skeletons to their death. Such a scene was painted many times, showing the plague specifically (and death more generally) as a great equalizer. Notke?s painting does not survive in its entirety and was damaged sometime during its history.

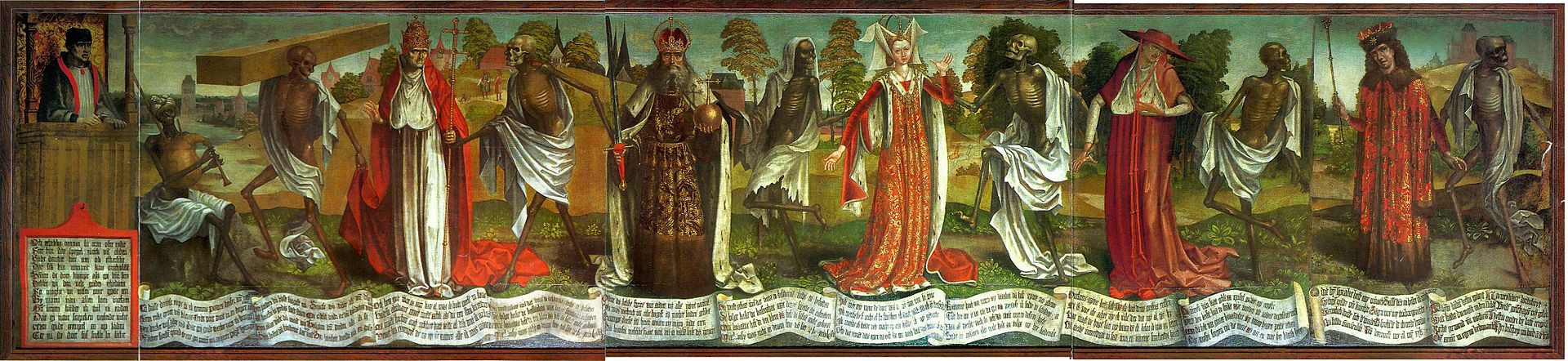

Many depictions of the danse macabre have not survived to the present day. Bernt Notke painted another version of the subject for Saint Mary?s Church in Lbeck. This elaborate depiction was lost during the bombing of the city in 1942. Though this original has been lost, the images were reproduced and, to a very limited extent at least, one is still able to appreciate the work.

Totentanz (?Dance of Death) Lbeck by Bernt Notke

Totentanz (?Dance of Death) Lbeck by Bernt Notke Totentanz (?Dance of Death) Lbeck by Bernt Notke

Totentanz (?Dance of Death) Lbeck by Bernt Notke

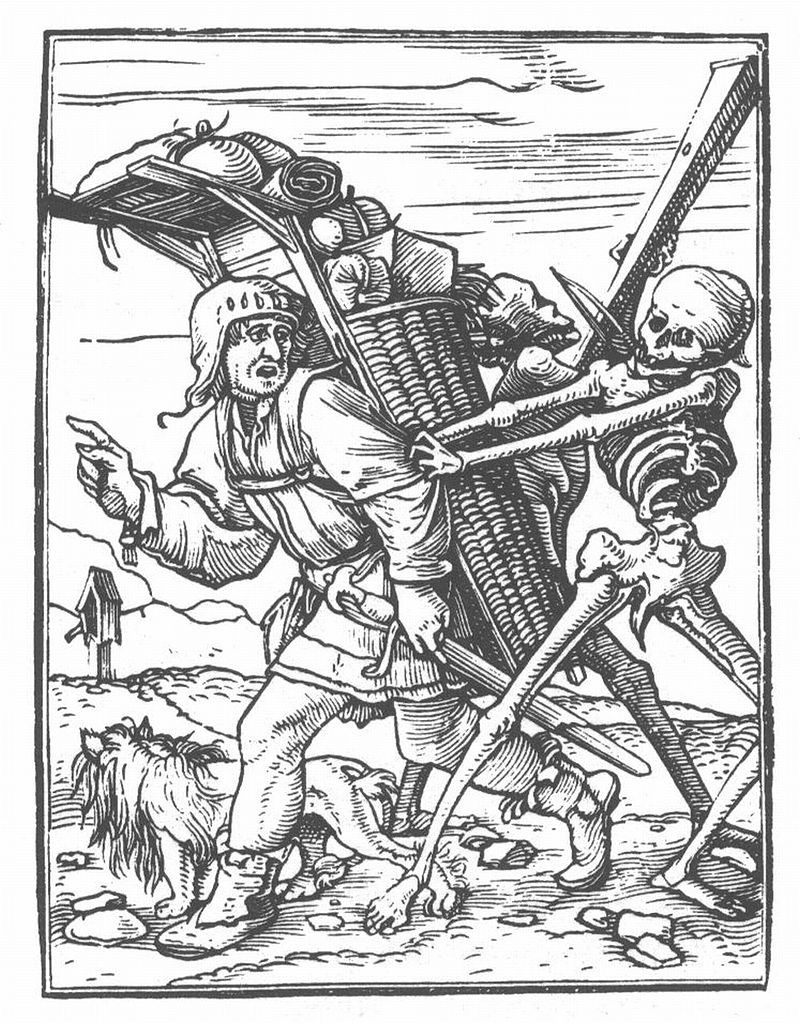

Danse macabre paintings survive throughout Europe. The theme was taken up by Michael Wolgemut in an image for the Nurnberg Chronicle of 1493 and Hans Holbein in the sixteenth century.

Dance of Death (1493), by Michael Wolgemut

Dance of Death (1493), by Michael Wolgemut death present in Holbein?s work, 1549

death present in Holbein?s work, 1549

The theme of ever-present death, skeletons dancing with people while taking them toward their graves, has influenced creatives for generations. In the nineteenth century, composer Camille Saint-Sans wrote a composition in 1874 called danse macabre:

When analyzing an period in human history, art is one of the most important sources to which one can go. Political power is transient. The artistic expression of each age contains the creative exploration of deep concepts by open-minded craftsmen and writers. Though statistics can tell us approximations about the deadly scope of the Great Mortality, the artworks reveal the impact on the human psyche. Bubonic plague remained a recurring problem from the mid-fourteenth century into the Age of Enlightenment.