Take a few moments to unlearn some dangerous myths.

In my years of teaching people about reptiles, I?ve found that most people think they have a good handle on telling a ?good snake? from a ?bad snake.? However, when we actually look at photos of different snakes, it usually turns out that only one or two attendees really know their stuff.

After a while, I noticed the main reason why some people repeatedly get IDs wrong. These are the folks that are stuck on using rules. Those that weren?t using these shortcuts were able to learn much faster. So, if you?ll give me fifteen minutes, I?d like to help you unlearn any rules you may have been taught. Oh, and by the way, there?s no such thing as a bad snake.

Before we begin, let me point out the only rule that works 100% of the time:

If you see a snake that you are not positive is harmless, simply take three steps back and walk away. You don?t need to kill wildlife to be safe!

Eastern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake exhibiting round pupils, photo by Rick Dowling

Eastern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake exhibiting round pupils, photo by Rick Dowling

I will start by admitting that there is usually some truth behind the rules people teach. The problem is that when you take a valid characteristic out of context and elevate it to some sort of litmus test, people usually misapply what could have been good information.

For example, it?s true that vipers do have elliptical pupils (also called cat eyes or slit pupils). Does that mean that all venomous snakes have elliptical pupils or that all snakes with this trait are venomous? No, both of those statements are false. You can?t take one feature like that and run wild with it.

If you really want to use a rule, you?ll need to learn a list of exceptions (trust me, there are exceptions). In my opinion, that approach is confusing. Plus, it?s too much work! You learn snake (or any animal) identification the same way you learn any other skill- by repetition.

Think about how you recognize the people you know. Do you go through a checklist like height, weight, or eye color? No, you simply know them when you see them because you have seen them several times before. I?d bet you?ve learned hundreds of corporate logos effortlessly this way as well. Repetition is the easiest and best way to learn identification.

In my opinion, venomous snake identification should be grade-school knowledge alongside not playing with fire and looking both ways before crossing a street. Maybe you?re just starting out and can?t tell a brownsnake from a baby copperhead, but that?s okay! There are only a few venomous snakes in your area, and you can learn what they look like without using shortcuts.

Rules are good at two things: getting people hurt and getting harmless snakes killed.

Blunthead Tree Snake (Imantodes cenchoa), a harmless Central American snake with elliptical pupils, photo by Myke Clarkson

Blunthead Tree Snake (Imantodes cenchoa), a harmless Central American snake with elliptical pupils, photo by Myke Clarkson

Rules Covered by this Article

- Triangular Head Shape

- Elliptical Pupils

- ?I Heard it Rattle!?

- Protruding Brow (supraocular scales)

- Heat-sensing (loreal) Pits

- Swimming Posture

- Mouth Color

- The Coralsnake Rhyme

First, a few snake basics?

There are two primary families of venomous snakes. Each family has various characteristics that make it unique. One of the main problems with rules is that they usually only address one family group and miss the rest. Let?s touch on these for just a moment.

Viperidae (Viperids)

This family contains pitvipers (such as rattlesnakes and moccasins that have heat-sensing pits between their eyes and nostrils), the Fea?s vipers of southeast Asia, and ?true? vipers (pitless vipers such as bush vipers or puff adders). Shared traits include retractable fangs, elliptical pupils, and heads that are distinct from their necks due to pronounced venom glands.

Timber Rattlesnake, a pitviper in the family Viperidae, photo by Mark Krist

Timber Rattlesnake, a pitviper in the family Viperidae, photo by Mark Krist

Elapidae (Elapids)

This family contains tropical and subtropical fixed-fang snakes such as seasnakes, coralsnakes, cobras, mambas, kraits, and taipans. These snakes have elongated venom glands that give their heads a more slender appearance. They also have fixed fangs in the front of their mouths. They do not have elliptical pupils and do not possess heat-sensing pits.

Variable Coralsnake, an elapid, photo by Armin Meier

Variable Coralsnake, an elapid, photo by Armin Meier

There are many other families of snakes, as well. You have surely heard of Boids such as the Boa Constrictor and Pythonids such as Burmese Pythons. The largest family is Colubridae, which accounts for over half of the world?s snakes. Colubrids are almost all harmless to humans, but there are a very few, such as the Boomslang and twig snakes of Africa, that are considered medically dangerous. There are other colubrids (e.g., hog-nosed snakes) with mild adverse compounds in their saliva that are technically considered venomous but do not pose a threat to humans.

Mexican Hog-nosed Snake, a harmless colubrid with tiny rear fangs. Photo by Mike Kolb.

Mexican Hog-nosed Snake, a harmless colubrid with tiny rear fangs. Photo by Mike Kolb.

As you can see, with such diversity among snakes, it is impractical to think that there could be any one ?rule? to cover them all. It is possible to learn their various differences and similarities, provided one does not try to over-simplify the learning process with quick tricks.

On to the rules?

Harmless Great Basin Gophersnake exhibiting the common defensive display of head flaring, photo by Andrew Nydam

Harmless Great Basin Gophersnake exhibiting the common defensive display of head flaring, photo by Andrew Nydam

Triangular Head Shape

In my informed opinion, head shape is by far the worst rule anyone could possibly use to determine if a snake is venomous or not. This commonly-used trick results in more harmless, beneficial snakes being killed than any other shortcut.

As we learned above, this rule stems from the fact that vipers (such as rattlesnakes and puff adders) do have pronounced venom glands that make their head larger than their neck. However, most snakes can and do flare their necks out to look menacing as a defensive display. Plus, many snakes have heads that naturally have a triangular or diamond shape.

An experienced observer can indeed tell the difference between these subtleties, but a novice (meaning someone who is trying to use this rule) almost always mistakes the natural head shape of harmless snakes as being triangular. This is perfectly understandable, as snakes provoke fear in many people, and fear and adrenaline cloud our judgment. The result is almost always someone over-reacting and killing harmless, beneficial snakes. PLEASE DO NOT USE OR TEACH THIS ?RULE.?

Here is a little head shape quiz. See if you can tell which of these snakes are venomous.

- VENOMOUS Yellow-bellied Seasnake, photo by Myke Clarkson

- HARMLESS Western Ratsnake, photo by John Whitney

- HARMLESS Gophersnake, photo by Joe Graves

- HARMLESS Eastern Hog-nosed Snake, photo by Tim Spuckler

- HARMLESS Florida Watersnake, photo by Kaylynn McKathan

- HARMLESS California Red-sided Gartersnake, photo by Tim Spuckler

Two through six are all perfectly harmless snakes that illustrate how nonvenomous snakes often have a triangular appearance. The first snake, indigenous to tropical seawaters including the US Pacific coast, is the only venomous snake in the quiz and it has a slender head. Hopefully, you?re able to see why so many people are so often mistaken when using ?triangular heads? as a rule. If you?re not convinced, join our ID group for lots more examples!

Indian Cobra, a venomous snake with round pupils, photo by Ashley Wahlberg

Indian Cobra, a venomous snake with round pupils, photo by Ashley Wahlberg

Elliptical Pupils

Were you taught that ?cat eyes? mean that a snake is dangerous? Lots of people believe this is the best ?test? or ?rule? for snake identification. This is another unreliable indicator when used by itself.

As we learned in the basics above, viperids do have elliptical pupils, but elapids do not. Likewise, many harmless snakes have this feature, including pythons, boas, as well as various colubrids such as cat-eyed snakes, leaf-nosed snakes, lyresnakes, nightsnakes, and others. The venomous colubrids mentioned earlier also have round pupils. In other words, there are lots of dangerous snakes with round pupils and lots of harmless snakes with ?cat eyes.?

This should be enough reason not to use pupil shape as a rule, but it?s not the only reason.

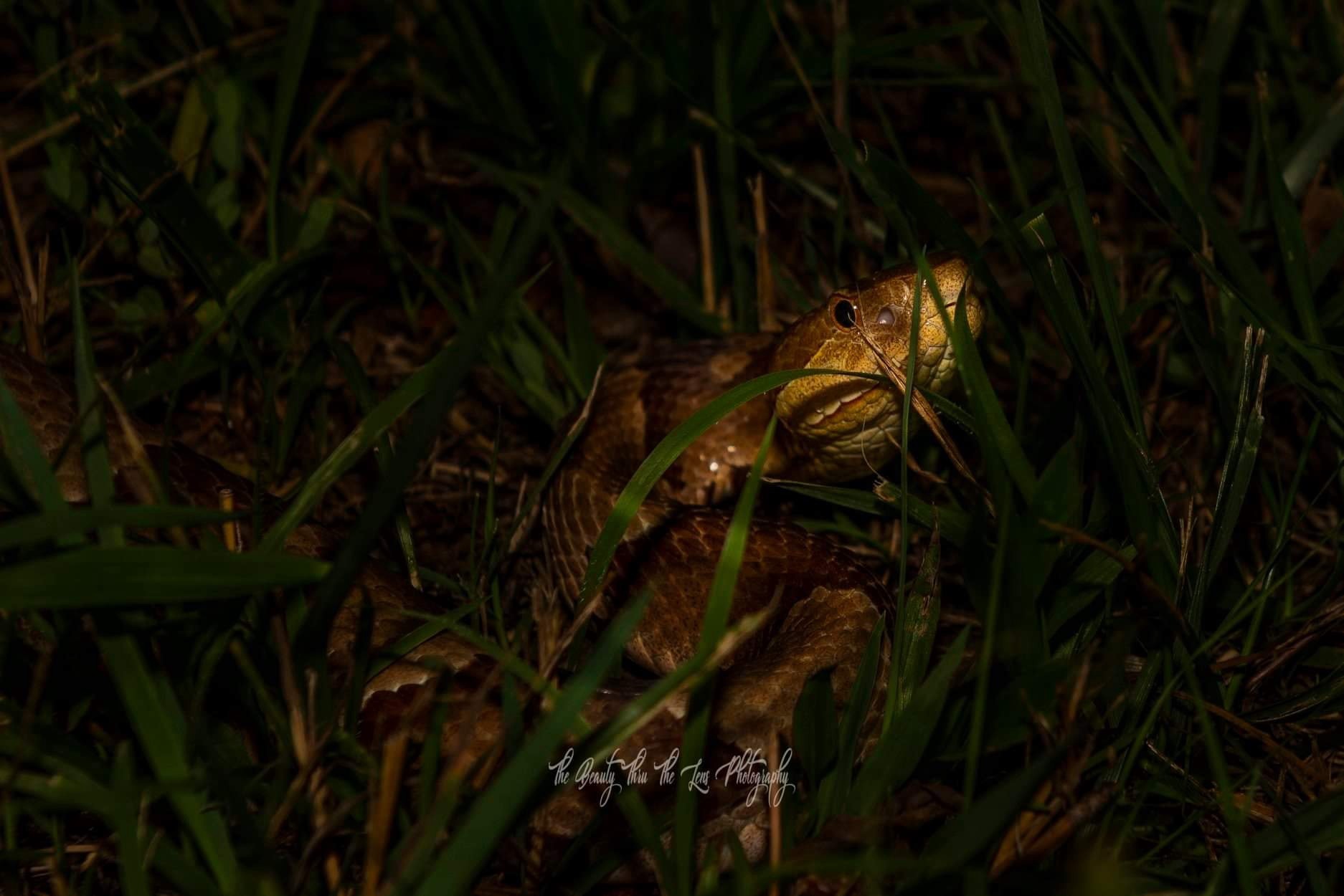

Eastern Copperhead exhibiting round pupils photo by The Beauty Thru The Lens Photography. This is just one example of why relying on overly simplistic rules for a correct identification is not recommended.

Eastern Copperhead exhibiting round pupils photo by The Beauty Thru The Lens Photography. This is just one example of why relying on overly simplistic rules for a correct identification is not recommended.

As illustrated in the photo above, the purpose of pupils is to regulate light intake to the retina, so ALL snakes have round pupils in low light. Since dusk to dawn is a common window to encounter snakes, this factor alone is enough reason not to rely on pupil shape for an ID.

This cottonmouth (above) and copperhead (below) are vipers that exhibit elliptical pupils. Photo by Ashley Wahlberg.

This cottonmouth (above) and copperhead (below) are vipers that exhibit elliptical pupils. Photo by Ashley Wahlberg.

For the sake of argument, though, let?s pretend for a moment that the rule about ?cat eyes? actually worked for snakes native to the US (even though it doesn?t). It would still be a dangerous shortcut because it is entirely possible to run across a nonnative animal (escaped or released pets or accidental transplants). Here is a recent news story about an escaped cobra in the US, illustrating how someone could get hurt if they thought that round pupils meant non-venomous.

Madagascar Leaf-nosed Snake, a harmless snake with elliptical pupils, photo by Brittany Williams

Madagascar Leaf-nosed Snake, a harmless snake with elliptical pupils, photo by Brittany Williams

On the flip side, you could easily run into a harmless nonnative with elliptical pupils. I am treating a perfectly harmless, friendly, and cute ball python at our shelter named Lucky. Lucky was a class pet that was released outdoors when the school didn?t want him anymore.

Lucky, who had only ever known the provision of captivity, wandered onto someone?s porch, presumably looking for care and assistance. Lucky was shot, severing his spine, because he has ?cat eyes,? ?snout pits,? and a ?triangle head.? Miraculously, he was found and brought to our clinic and is healing up nicely. Lucky is a harmless, sweet snake that got hurt because of bad rules.

Lucky is a harmless pet python that was shot, severing his spine, after someone used rules to decide he was dangerous.

Lucky is a harmless pet python that was shot, severing his spine, after someone used rules to decide he was dangerous. Timber Rattlesnake photo by Justin Sokol

Timber Rattlesnake photo by Justin Sokol

?I heard it rattle!?

I have lost count of the times an upset mother has called me insisting that ?there?s a rattlesnake on my carport!? Every time, I get there to find a harmless ratsnake. Where rattlesnakes occur (and even places they don?t!), many people assume that any snake making a rattling noise is automatically a rattlesnake.

In fact, a great many harmless species will make noise by vibrating their tail against leaves or debris. This is another defensive mechanism ? the animal is trying to sound and look as imposing as possible in response to being approached by a huge potential predator. On the other hand, rattlesnakes often make no sound and may even be missing their iconic rattle as a result of it getting hung and broken off.

So, you may hear a rattling sound from a harmless snake, or you may run across a rattlesnake that doesn?t make any noise. You are definitely better off not treating this as any kind of rule.

Harmless Florida Watersnake (left) compared to a venomous Florida Cottonmouth (right) illustrating the difference in the visibility of the eyes from above, photos by Luke Smith

Harmless Florida Watersnake (left) compared to a venomous Florida Cottonmouth (right) illustrating the difference in the visibility of the eyes from above, photos by Luke Smith

Protruding Brow (supraocular scales)

Okay, so again we have a rule that is based on a useful identification trait. Viperids do have pronounced scales (called supraocular scales) above their eyes. The photo above illustrates how one might use this knowledge. If you are viewing a snake from above, a viper’s eyes will be obscured by these scales.

I?m sure you can guess the safety implications of using this as your main go-to for identifying snakes. If you don?t already know what kind of snake you are looking at, you should NOT be standing over it looking down. Another big problem with using this as a venomous/harmless marker is that elapids do not have this feature (a few, like the King Cobra, have slightly pronounced supraoculars, but not to the same degree). So this feature, even when correctly applied, misses an entire family of venomous snakes (plus the oddball venomous colubrids).

Other than that, this one can trip people up when they are looking from a side angle. As you can see in the photo below of a harmless coachwhip, lots of other snakes have a slightly protruding ?brow.? I have met people who say they use this feature to tell if a snake ?looks mean? and those are the ?bad ones.? Someone with little to no experience identifying snakes is going to think they are seeing pronounced supraoculars in a lot of snakes. All in all, this is a good thing to know, but it has to be applied properly.

Harmless Eastern Coachwhip photo by Justin Sokol

Harmless Eastern Coachwhip photo by Justin Sokol Eastern Copperhead, a pitviper, photo by Justin Sokol

Eastern Copperhead, a pitviper, photo by Justin Sokol

Loreal (heat-sensing) Pits

As you can see in the photo above, vipers such as this Eastern Copperhead have what are called loreal pits located between their eyes and nostrils. They have one on each side, and they are larger than the nostril. These are incredible features that enable them to essentially ?see? heat signatures. This greatly facilitates their strike efficiency and is a fascinating subject of study (see Snakes That Can See Without Eyes for more info). Unfortunately, some people have taken this information and use it as a rule, saying that pits are how you know a snake is venomous.

There are a few issues with using this as a rule, not the least of which is that you shouldn?t be close enough to make this feature out if you are not already sure what snake you are looking at! Usually, loreal pits are not as easy to see as the photo above might lead you to believe. I have also seen lots of people confuse nostrils with loreal pits.

Next, not all vipers have loreal pits- just the pitvipers (ergo the name). So this rule doesn?t even cover all the snakes in the family Viperidae. Elapids also do not have heat pits, so it misses that entire family of venomous snakes that occur all over the world in tropical and semi-tropical regions (such as coralsnakes).

Green Tree Python, one of many harmless snakes with heat-sensing openings CC0

Green Tree Python, one of many harmless snakes with heat-sensing openings CC0

Yet another issue with this is that pitvipers are not the only snakes with heat-sensing organs in their snout. Snakes in several other families exhibit this feature, many of which are common in the pet trade and therefore more likely to be encountered outside their natural range.

As you can see, this is a genuine feature to look for in pitvipers, but it has too many glaring issues and exceptions to be of any use as a rule.

Cape Cobra, lacking heat pits like all venomous elapids, photo by Bionerds

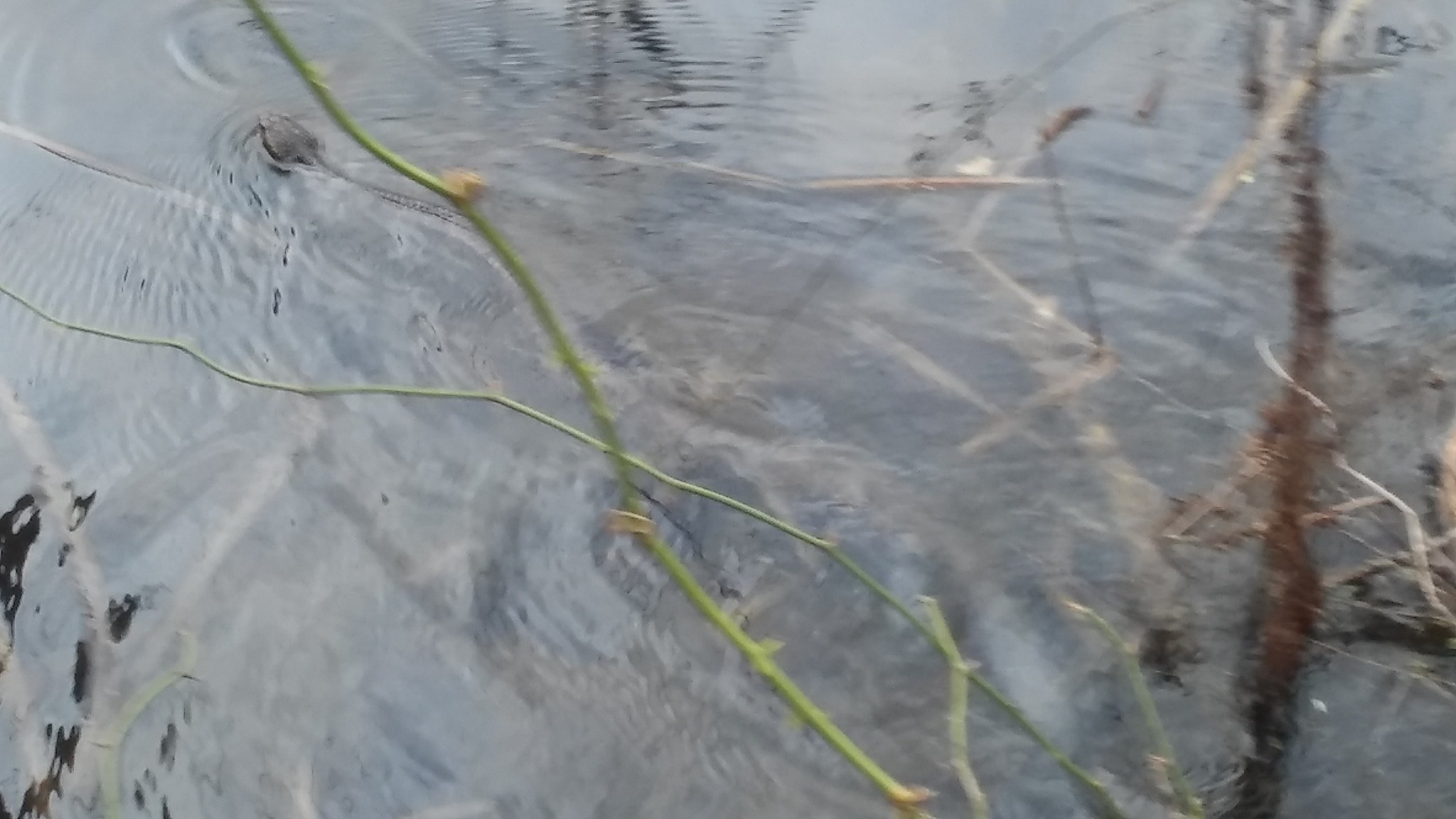

Cape Cobra, lacking heat pits like all venomous elapids, photo by Bionerds Northern Cottonmouth swimming with its body below the water, photo by Gary Lee

Northern Cottonmouth swimming with its body below the water, photo by Gary Lee

Swimming on top of the water

This is another one with a grain of truth. Some venomous snakes, particularly moccasins, do have a tendency to swim on top of the water. They do this by inflating their lung to become more buoyant. These snakes are ambush predators and sometimes even hunt this way by laying on the water and grabbing a fish or amphibian that happens by.

However, I always say that snakes don?t read books and often don?t know they?re ?supposed? to swim in a certain fashion. It is not all that unusual to see a venomous snake swimming with its body submerged. Neither is it uncommon to see a harmless snake swimming on top of the water. Any snake is capable of swimming however it wants.

So, it may be okay to look at the posture of a snake in the water and think to yourself, ?that snake is swimming like a cottonmouth,? but you still need to look at the snake closely to see if you are right. Jumping to conclusions will result in errors more often than you might think.

Florida Cottonmouth exhibiting their characteristic mouth gaping behavior, photo by Luke Smith

Florida Cottonmouth exhibiting their characteristic mouth gaping behavior, photo by Luke Smith

White Mouths

It took me a while to add this rule because it didn?t occur to me that people would need clarification, but it seems many do. Cottonmouths are well-known venomous snakes in the US. Harmless snakes are misidentified as cottonmouths so often that is has passed being funny and is just sad at this point. One of the reasons is that many people think that any snake with a white lining in its mouth is automatically a cottonmouth.

You should not use the color of a snake?s mouth to determine if it is venomous. While not all snakes have white mouths, white is an extremely common coloration. Cottonmouths do have white mouths, but they did not get their name for being unique in that regard. In fact, you can?t even use this to rule out an ID of cottonmouth, as their mouths often appear pinkish.

Cottonmouths got their name from their frequently-used defensive display of ?gaping? at an approaching threat. They open their mouths and show off their white lining as a warning sign. They don?t want trouble any more than you do, so they hope that flashing a warning will steer you away. For more info, read You?re Getting Too Close or The Maligned Cottonmouth.

Harmless Western Ratsnake, a species that commonly gets misidentified because of their white mouths, photo by Johnathan Ellard

Harmless Western Ratsnake, a species that commonly gets misidentified because of their white mouths, photo by Johnathan Ellard A Texas Gulf-coast Coralsnake exhibiting normal coloration, photo by Ashley Wahlberg

A Texas Gulf-coast Coralsnake exhibiting normal coloration, photo by Ashley Wahlberg

The Coralsnake Rhyme

First, what is the rhyme? It comes in different flavors, but the basic version is, ?Red touches yellow will kill a fellow, red touches black is a friend of Jack.? The colors refer to the tri-colored (black, red, and yellow) banding on venomous US coralsnakes and some of their mimics (similar-looking harmless snakes).

Let?s start with a little quiz. In the following illustration, see if you can use the rhyme to determine which of these species would be safe to pick up if one got into your house. I?ll give you the answers in a moment.

In all fairness, like most rules, the rhyme is based on a certain truth, but there are extra parameters that no one explains.

- Even though coralsnakes occur in many countries, the rhyme is only meant to apply in the United States.

- The rhyme gets misremembered. One of the ways I have heard this is, ?Red touches yellow?s a friendly fellow; Red touches black, you?d better get back.? A young woman got envenomated just a few months ago because she asked if a coralsnake was venomous on Facebook and someone said the rhyme wrong. If you are facing a snake that you think could hurt you and you get an adrenaline rush, how easy do you really think it will be to properly recite and decipher a rhyme that you may not have heard in years? In my opinion, you are better off memorizing what your local snakes look like so you don?t have to think about it.

- The rhyme assumes that you are looking at a normally-colored snake. While most snakes do have a predictable appearance, aberrancies (oddly-colored individuals) are common enough that we see them regularly on the snake forums.

- The rhyme presumes that you know how to interpret what it means more than what it says. For example, on the (normally-colored) Texas Coralsnake above, you can see that the black bleeds past the yellow bands. Consequently, the red is touching yellow and black. The rhyme is referring to the yellow in this instance, but that is not mentioned.

- The rhyme presumes that you either live in an area without species that break this rule, or you already know which other snakes to exclude. Here?s a tidbit you might not have known: there are more harmless species (four) in the US alone that have red touching yellow than there are species of coralsnakes in the US (three). Let me say that again, in case it didn?t sink in.

There are more harmless species in the US that fit the ?kill a fellow? part of the rhyme than there are coralsnakes that the rhyme is designed for.

You are encouraged to look that last part up if you are skeptical. I will even tell you what they are: the Resplendent Desert Shovel-nosed Snake, Chionactis annulata; the Mohave Shovel-nosed Snake, C. occipitalis; the Sonoran Shovel-nosed Snake, C. palarostris, and the Long-nosed Snake, Rhinocheilus lecontei. The three species of indigenous coralsnakes are the Harlequin Coralsnake, Micrurus fulvius; the Texas Coralsnake, M. tener; and the Sonoran Coralsnake, Micruroides euryxanthus.

Now, granted, not all of these species overlap, but do you know if you are in an area where more than one of these occur? I?d wager most people don?t. The rhyme does not clarify any of this. (Since you?re probably wondering, the shovel-nosed and long-nosed snakes occur in the southwestern US, so if you are east of the Mississippi River, you?re not likely to run into those.)

Let me get one more gripe out of the way about the rhyme. US coralsnakes bites are painful, but deaths are extremely rare. You are far more likely to become president of the United States than you are to die from a US coralsnake, but the rhyme makes it sound like they are unusually dangerous. With all of the fear and unnecessary hype around snakes, I don?t think that extra push is helping anything.

I could keep listing objections, but let?s get back to our quiz. You?ve heard the rhyme and you?ve heard several caveats to consider. Do you want to scroll back up and try one more time before I give you the answers? Last chance!

- HARMLESS Sonoran Shovel-nosed Snake (US & Mexico), Chionactis palarostris, photo by COLEJWOLF

- VENOMOUS Aquatic Coralsnake, Micrurus surinamensis (South America), photo by Bernard Dupont

- VENOMOUS Bibron?s Coralsnake, Calliophis bibroni (India), photo by Prasenjeet Yadav

- VENOMOUS Variable Coralsnake, Micrurus diastema (Mexico), photo by Luis Diaz-Gamboa

- HARMLESS Long-nosed Snake, Rhinocheilus lecontei (USA), photo by Amy

- VENOMOUS Texas Coralsnake (melanistic), Micrurus tener (USA), photo by Tyler Sladen

So, how many did you get right? I bet if you got more than one right, it is because you already know your snakes and not because of a rhyme. Nonetheless, people cling to this rhyme like it was Scripture. Whether you choose to use it is entirely up to you, but I know I don?t allow it as a teaching tool in my classes or groups.

Conclusion

I hope by now you are getting the gist. Rules usually start with legitimate traits, but people distort these traits when they misapply them.

While it is true that some reputable herpetologists still teach some of these rules, I think it is better to simply take a little time to learn what the snakes around you look like. I recommend that everyone own a quality field guide and join an identification group in order to see many photos of snakes.

Shortcuts seem like they would make the process go faster, but there is an old saying that goes, ?Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.? Repetition is how we learn a new skill. Trying to rush the process results in more errors. I like to say, ?If you need a rule, you?re often going to get it wrong. If you know your snakes, you don?t need a rule!?

Happy herping, and don?t forget to join LIVE Snake Identification and Discussion on Facebook!

If you liked this story, you?ll also love these. Check them out next!

Stop Killing Snakes!

It?s cruel. It?s unnecessary. It?s pointless. Just stop it!

medium.com

Snakes Do Not Chase People!

Just because you run from something does not mean it is chasing you.

medium.com

Western Ratsnake photo by the author

Western Ratsnake photo by the author

The shortlink to share this story is bit.ly/Snake-ID

Do you like learning about reptiles, amphibians, and cooperating with nature? Be sure to follow The Natural World here on Medium!

You can also follow our wildlife center on Facebook, join our Snake Identification Group, or download the book (for free!) that this information came from, A Primer on Reptiles & Amphibians: A Collection of Educational Nature Bulletins, from our website.

Did you know? I give in-person presentations on this and similar topics at no charge. If you are within a reasonable driving distance from NW Louisiana, visit our website to discuss me speaking to your group.

The Natural World is looking for writers and photographers interested in helping us deliver science-based, interpretive stories about our natural heritage. If you?d like to discuss becoming a part of our team, drop us a line!