A disruptive work of modern art that continues to inspire

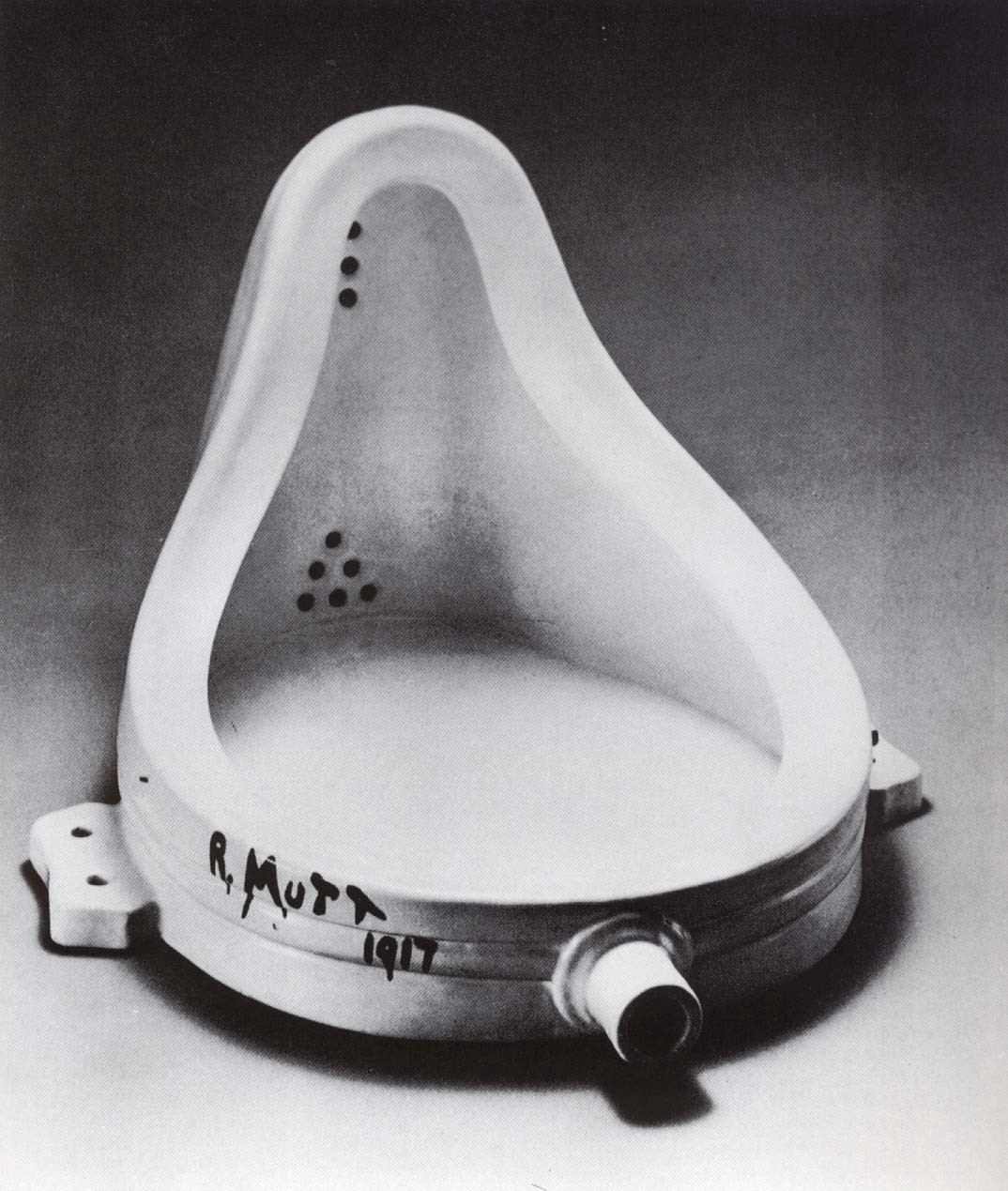

?Fountain? (1917) by Marcel Duchamp (replica). Source Wikimedia Commons

?Fountain? (1917) by Marcel Duchamp (replica). Source Wikimedia Commons

To my mind, there are few works of art that have had such a distinct and emphatic influence on the course of art than Marcel Duchamp?s Fountain, made in 1917.

Fountain is a porcelain urinal. There is little else to say about it. It?s a urinal. Except that, in April 1917, Duchamp had the temerity to submit it to the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists as a work of art.

Fountain is a so-called ?readymade? sculpture, meaning that it is an ordinary, manufactured object that the artist has simply selected and perhaps modified in some way. Duchamp made very little modifications to the object, except turn it on its side and sign it with a pseudonym ?R. Mutt?.

Many words have been expended on this strange artwork, as if its very presence in our cultural landscape needs more justification than any other work of art. Perhaps it does. The very contentiousness of Fountain means it has survived its historical moment and continues to impress upon us its combative punch, not to mention inspiring the interests and practices of several generations of later artists.

That contemporary art is not universally loved bears heavily on Fountain, since whatever else Duchamp was trying to achieve (or mischieve), he certainly meant to create something disagreeable. Contemporary art endures many of its sharpest criticisms because of Duchamp?s daring and provocative example.

Intentionally Disruptive

In the 21st century, we are familiar to the term ?disruptive?. In its positive form it means to be innovative or groundbreaking, usually applied to business models that create new ?value networks? within the marketplace. In other words, to disrupt is to shake up the customary way of doing things.

Disruption is a useful paradigm to understand Fountain. As one of the first postmodern statements in art, the work is meant to unsettle our customary assumptions about what a work of art ought to look like.

Fountain has none of the hallmarks of a typical artwork we might expect to find in a gallery. It is not a painting, nor is it a sculpture in any traditional sense. The artist behind the work has done little except pick out the object and place it on a plinth. The ?skill? behind it is minimal. He hasn?t even signed it with his own name (R. Mutt was a joke by Duchamp: Mutt comes from Mott Works, the name of a large sanitary equipment manufacturer).

Duchamp?s foremost intention was to test the rules of the Society of Independent Artists. How would they react to a work that was, to all intents and purposes, a urinal? When Duchamp submitted the work to the exhibition, he knew that, since he had paid the entrance fee, it was against the rules of the society to reject it. He wrote later:

No, not rejected. A work can?t be rejected by the Independents. It was simply suppressed. I was on the jury, but I wasn?t consulted, because the officials didn?t know that it was I who had sent it in; I had written the name ?Mutt? on it to avoid connection with the personal. The ?Fountain? was simply placed behind a partition and, for the duration of the exhibition, I didn?t know where it was. I couldn?t say that I had sent the thing, but I think the organizers knew it through gossip. No one dared mention it. I had a falling out with them, and retired from the organization. After the exhibition, we found the ?Fountain? again, behind a partition, and I retrieved it!

Of course, Duchamp wasn?t trying to compete against traditional painting and sculpture with his readymade. Rather, he was making a disruptive claim about what art can be. If something is presented as art ? if the artist says it?s art ? then who is to say whether or not it qualifies?

What art is, or what constitutes art, are questions that have consistently foxed philosophers and theorists. Different places and different ages have found their own answers to this question, which suggests that any permanent, stable definition of art is impossible to pin-down. Duchamp?s act in proclaiming Fountain as a work of art is reliant precisely on the inherent instability of the term.

In this way, its status as an artwork emerges from the intentions of the artist, a conceptual sleight-of-hand that, like the famous rabbit-duck illusion, flips ambiguously between greatness and silliness depending on how you look at it.

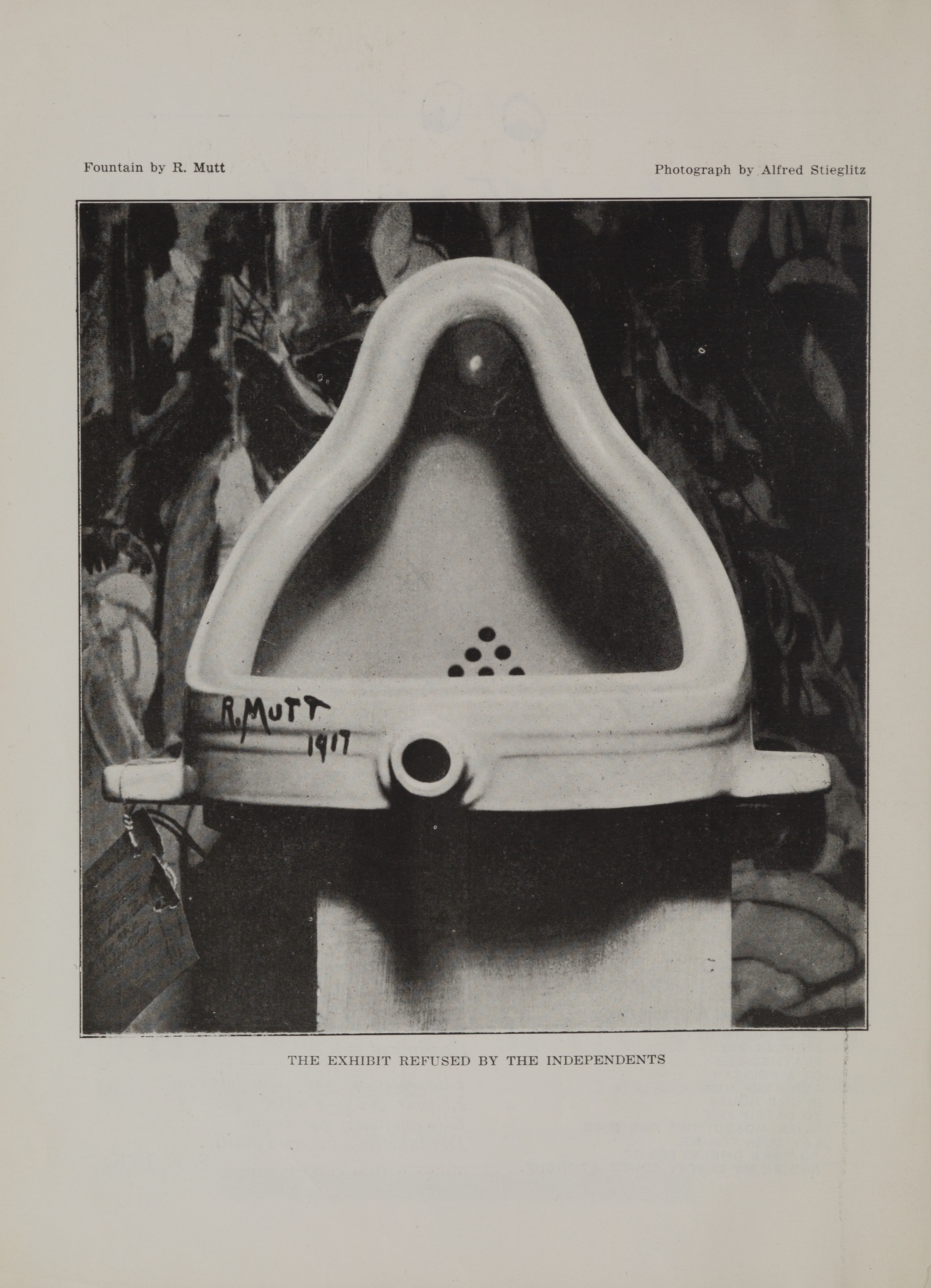

Marcel Duchamp ?Fountain?, 1917, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz at 291 (art gallery) following the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, reproduced in ?The Blind Man?, ?2, New York, 1917. Source Wikimedia Commons

Marcel Duchamp ?Fountain?, 1917, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz at 291 (art gallery) following the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, reproduced in ?The Blind Man?, ?2, New York, 1917. Source Wikimedia Commons

The extraordinary thing about Fountain is its lasting influence. As an act of postmodern provocation, it has become an exemplar of a new means of inquiry. It symbolically addresses the wider assumptions of cultural tradition, habits of thought and the role of museums in regulating what we as a society deem noteworthy or merely ordinary.

Postmodernism?s core principles would later emerge as complexity and contradiction, wherein ideas of stability, progress and utopianism were open to question. Postmodernist art ? beginning with Duchamp?s Fountain ? is restless in this sense. To arrive at a single point of view seems inadequate. Change is everywhere about us, so our perspectives must continue to change too. Contemporary art continues to have these ideas at its heart.

The influence of Fountain has not lessened over time. Artists continue to ask the same sorts of questions, using their art to probe how and why we hold the cultural values we do. And by adopting the position that anything can be a work of art, then the breadth and array questions becomes almost infinite.

As a measure of its lasting impact, in 2004, nearly a hundred years after its conception, Duchamp?s Fountain was voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 selected British art world professionals.

Christopher P Jones writes about art and culture at his website.