Listen to this story

–:–

–:–

YOUTH NOW

Even under ?restricted mode,? the platform is showing kids some truly vile programming

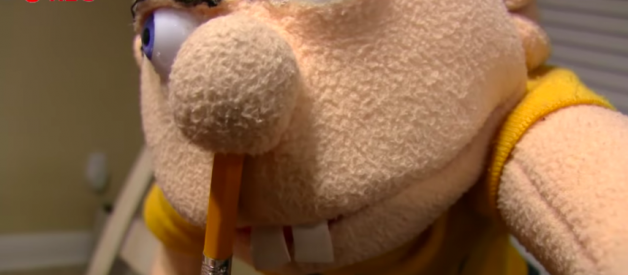

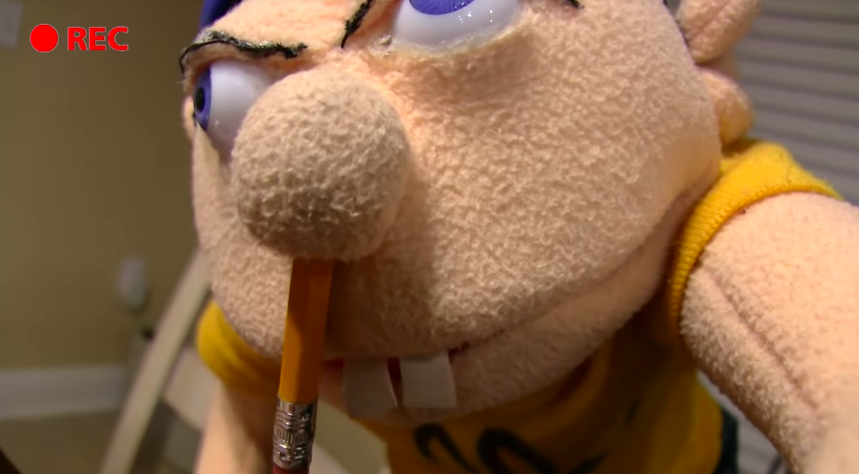

Screencap via SuperMarioLogan YouTube

Screencap via SuperMarioLogan YouTube

In the summer of 2017, John Cook, a writer and editor living in the suburbs of New York, noticed that his three young kids, all boys, had become enamored with a mysterious figure known as Jeffy. His eldest son, nine-year-old H. (we?ve agreed to identify them by their initials due to their ages), mentioned his name while joking around with a friend from his fourth-grade class, adopting an odd speech impediment whenever they quoted something Jeffy had said. Later, Cook heard his youngest, W., a preschooler, singing a song including double entendre about exposing himself: ?Wanna/see my/pencil?? Under parental interrogation, he attributed the lyrics to Jeffy. By then, his boys were talking about Jeffy all the time.

In the summer of 2017, John Cook, a writer and editor living in the suburbs of New York, noticed that his three young kids, all boys, had become enamored with a mysterious figure known as Jeffy. His eldest son, nine-year-old H. (we?ve agreed to identify them by their initials due to their ages), mentioned his name while joking around with a friend from his fourth-grade class, adopting an odd speech impediment whenever they quoted something Jeffy had said. Later, Cook heard his youngest, W., a preschooler, singing a song including double entendre about exposing himself: ?Wanna/see my/pencil?? Under parental interrogation, he attributed the lyrics to Jeffy. By then, his boys were talking about Jeffy all the time.

Jeffy, as Cook later learned, is a recurring character in an online video franchise commonly known as Super Mario Logan, which includes a network of overlapping social media channels, primarily on YouTube, with derivative titles like Super Luigi Logan and Super Bowser Logan. Over the past 10 years, Super Mario Logan has published hundreds of videos featuring a mix of brand-name plush dolls and store-bought puppets. Manipulated and voiced by off-screen humans, they act out scenes and storylines ranging from gross and offensive to simply bizarre. Jeffy usually appears wearing a blue helmet and a diaper, with a wooden pencil protruding from his right nostril. He is one of most visible personalities within the Super Mario Logan universe, the constituent channels of which have accrued more than 9 million followers on YouTube alone. Cook?s two oldest sons got hooked on the series after a playdate with a neighbor?s kid, who played a few of the videos on his iPad. Before long, the youngest Cook boy was watching them too.

Cook?s introduction to the world of Super Mario Logan coincided with growing efforts to understand children?s relationship with YouTube.

But when Cook got around to watching SML for himself, he was alarmed by what he found: an array of racist stereotypes, misogynist humor, homophobic jokes, and worse, smuggled into videos that are clearly aimed at children. A character named Jackie Chu, for example, is portrayed by a puppet who, as his Fandom entry explains, ?pronounces things wrong such as ?Cacurus? (Calculus), ?Rawn? (Wrong), ?Crass? (Class)? and cannot see as well as others, due to his eyes being squinted too tightly.? Another character, Black Yoshi, speaks in an exaggerated form of African-American Vernacular English, shoots and kills other characters with a plastic gun, and is otherwise portrayed as an illiterate deadbeat solely concerned with playing video games. One of the videos Cook came across, titled ?Black Yoshi?s Job Interview!,? opens with the following exchange:

Mario: Ugh, Black Yoshi, look what just came in the mail!

Black Yoshi: Ooh, my welfare check?

Mario: No, Black Yoshi, not your welfare check, this month?s bills! ?

Black Yoshi: Mario, man, you knows I can?t read!

Women and gay people fare no better in other, related videos. A recurring character named Judy Nutkiss is written as a flamboyantly promiscuous and drug-addled idiot. Judy?s openly gay son, Cody, is depicted as a perverted 10-year-old who routinely has sex with a Ken doll.

Cook?s introduction to the world of Super Mario Logan coincided with growing efforts to understand children?s relationship with YouTube. This was driven, in part, by the platform?s immense popularity among young people: Pew Research recently reported 85 percent of U.S. teens use YouTube on a daily basis. Last year, the research firm Smarty Pants found 83 percent of surveyed children between six and 12 years old do the same. But it was also driven by questions about what, exactly, kids are consuming through the platform.

In early 2017, journalists began to document an explosion of low-quality videos that placed popular brand-name cartoon characters in violent, obscene, or otherwise inappropriate scenarios. In February, the Verge and the Awl took note of videos depicting Elsa, of Disney?s Frozen franchise, defecating, being urinated on, wearing only underwear, giving birth, and more. In March, the Outline highlighted knockoff videos showing Peppa Pig, the titular character of the British children?s series, in disturbing or traumatic encounters, such as a sadistic dentist, armed with a large syringe, removing the character?s teeth.

At first, YouTube counseled parents of young children to flag any inappropriate videos for manual review and to restrict their kids? ability to search for new videos. But as the controversy picked up intensity, eventually earning the name Elsagate, YouTube?s response became more forceful. In June 2017, the platform vowed to pull ads from videos that made ?inappropriate use of family entertainment characters? and later added new, more aggressive filters to restrict the spread of such videos. In December, YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki promised to add more human moderators and expand the company?s machine-learning moderation tools.

Welcome as the changes are, YouTube?s system for moderating and filtering videos remains a confusing mess of options. (The website?s ?restricted mode,? for example, uses different filtering criteria than its more restrictive YouTube Kids app.) Furthermore, Cook?s experience demonstrated that YouTube may not have the answers to all the problems created by its platform. Many of its various roles ? entertainer, educator, babysitter, moneymaker, and censor ? often conflict with one another. Caught in the middle are parents like Cook and video makers like the man behind Super Mario Logan. It?s not yet clear if they can live in harmony, or if we should want them to.

Netflix exerts complete control over what appears on the service, and all content is screened and tagged beforehand. YouTube, on the other hand, allows anyone to upload almost kind of video to its platform.

Super Mario Logan is the creation of a 23-year-old man named Logan Thirtyacre, who lives in Pensacola, Florida. According to crowdsourced biographies on websites like Fandom and Know Your Meme, Thirtyacre has been uploading short videos to YouTube since late 2007, beginning shortly after his 13th birthday. In the decade since, SML has expanded to include dozens of characters (some of whom possess several alter egos), hundreds of plots and backstories, and a handful of puppeteers and voiceover actors. Thirtyacre?s body of work, more than 800 videos in all, includes an array of narratives about the characters, secondary narratives about Thirtyacre?s friends and colleagues, and an ongoing chronicle of his tumultuous relationship with YouTube itself. Most videos take place in conspicuously domestic settings, many of which appear to be in Thirtyacre?s own home. The unlikely result is a sprawling world ? part Meet the Feebles, part Tolstoy, part toilet stall graffiti ? designed to entice and amuse and offend, in precisely equal measures.

Presumably, SML is very, very lucrative. Although concrete numbers are hard to come by, and Thirtyacre did not respond to emails seeking an interview, AdSense research and somewhat sketchy online sources suggest the franchise could be bringing in yearly revenue in the high six figures, and likely more. Complicating matters, however, is Thirtyacre?s vulnerability to demonetization, the inartful term for YouTube?s habit of pulling advertisements from a particular channel or video. In February, Thirtyacre announced on Instagram that the platform had abruptly demonetized the main channel, Super Mario Logan; he redirected his followers to Super Luigi Logan instead. Whatever his income, Thirtyacre has been putting it to use. He owns a five-bedroom house in Pensacola under his own name and has registered multiple private companies in Florida, according to state business and property records. More recently, he acquired a cherry-red Lamborghini Huracan Performante, which sells for $310,000.

While it?s difficult to determine the precise demographics of any online following, one thing is clear: A great number of Thirtyacre?s devotees are young children like Cook?s. And you don?t have to be a child development expert to realize the addictive appeal, for kids still in elementary school, of videos featuring beloved cartoon characters acting out taboo scenarios in settings resembling their own homes. Cook?s middle child, seven-year-old S., found this combination so appealing that he recommended SML to his peers. ?I would totally say, ?Hey, you should watch this. It?s really funny,?? he said.

As a career journalist who once served as editor in chief of Gawker, Cook was not a stranger to the darker tendencies of the internet. Certainly, he had seen much worse than Super Mario Logan. But it aggravated him that his kids were able to view these videos in the first place. Indeed, he had taken steps to ensure they couldn?t. H., his oldest son, is allowed to watch Netflix and YouTube as long as certain restrictions are in place. On Netflix, Cook had enabled ?parental controls,? which filter shows and movies based on their maturity level (ranging from ?for little kids only? to ?all maturity levels?). On YouTube?s website, he turned on ?restricted mode,? which the company describes as an ?optional setting that you can use to help screen out potentially mature content that you may prefer not to see or don?t want others in your family to see.?

At first glance, these systems may seem similar. But, as Cook was beginning to realize, they aren?t really comparable at all. Netflix exerts complete control over what appears on the service, and all content is screened and tagged beforehand. YouTube, on the other hand, allows anyone to upload almost kind of video to its platform. This is why its restricted mode is couched in buyer-beware terms: ?Due to differences in cultural norms and sensitivities, the quality may vary.?

Adding to the complexity, YouTube?s restricted mode is only one component of the platform?s content-filtering apparatus, and each of its components work in slightly different ways. For example, YouTube can restrict certain videos to older age groups when those videos ?don?t violate our policies, but may not be appropriate for all audiences.? It also operates a completely separate app, called YouTube Kids, that offers parents more granular control over what their kids can watch. But YouTube Kids is available only on smartphones and tablets. The app and website?s restricted mode follow different rules about acceptable content: A video that?s blocked on the Kids app won?t necessarily be blocked by restricted mode. Whereas YouTube Kids employs ?a mix of filters, user feedback, and human reviewers,? according to the company, restricted mode considers ?many signals ? such as video title, description, metadata, Community Guidelines reviews, and age restrictions ? to identify and filter out potentially mature content.? That?s how Cook?s oldest son was able to watch a selection of SML videos (though not all of them) on his Chromebook.

YouTube says its restricted mode is not designed to filter content for children.

Cook?s mixture of concern and bewilderment gradually turned into anger. ?There is a long history of highly calibrated, finely wrought regulation around what it is acceptable to show and market to children via television, and that entire architecture has been utterly thrown out the window in favor of blind algorithms engineered for maximum profit,? he told me.

It?s true that some television aimed at children is subject to government regulations that arose from societal concern about the medium. But those regulations, which mostly concern educational programming and food-related advertising, are something of a historical and technical anomaly, made possible by the U.S. government?s ownership of the physical broadcasting spectrum. Unlike your favorite local news affiliate, YouTube is not beamed into nearby homes via radio waves. Whether that distinction ought to matter is an increasingly fraught question for YouTube, whose executives have criticized efforts to regulate the platform more aggressively.

Contacted for this article, an unnamed spokesperson for Google, YouTube?s parent company, pointed to the terms of service, which instruct people younger than 13 not to use the platform. YouTube says its restricted mode is not designed to filter content for children, either. ?To be clear, Restricted Mode is not intended for kids under 13,? the spokesperson said in an emailed statement. They emphasized that videos uploaded to YouTube do not immediately appear on YouTube Kids: ?We use machine learning and algorithms to determine which content is available in the Kids app ? and this process usually takes several days.?

A charitable interpretation of YouTube?s philosophy would recognize that platforms dependent on user-created content can?t make any honest guarantees about the quality of that content. A less charitable interpretation might posit that YouTube is leveraging parental anxiety about the internet to gain access to the developing minds of children to sell even more ads and better train the platform?s recommendation algorithms.

This argument received a great deal of attention late last year, when several news outlets, including the New York Times and the Outline, reported on the proliferation of seemingly benign but, in fact, fairly disturbing YouTube videos featuring popular cartoon characters like Peppa the Pig and Mickey Mouse. One of these videos, the Times reported, ?was a nightmarish imitation of an animated series in which? some characters died and one walked off a roof after being hypnotized by a likeness of a doll possessed by a demon.?

In a widely read Medium essay published around the same time, British writer James Bridle declared a state of emergency: ?Someone or something or some combination of people and things is using YouTube to systematically frighten, traumatise, and abuse children, automatically and at scale.? The essay cited a crudely animated video in which Peppa the Pig ?is basically tortured? by a dentist. More frightening, though, was its suggestion that these videos were created by an advanced and possibly malevolent artificial intelligence. Only an algorithm, he argued, would title a video ?Wrong Heads Disney Wrong Ears Wrong Legs Kids Learn Colors Finger Family 2017 Nursery Rhymes.?

Thirtyacre obviously traffics in racist tropes and taboo humor. He also clearly understands how to use storytelling and stagecraft to connect with and hold the attention of young children.

SML has not attracted the same amount of attention, in part because its videos are obviously created by human beings. But the franchise hasn?t escaped criticism. In December, a woman in Teesside, England told a local newspaper that an SML video featuring Jeffy inspired her seven-year-old son to wrap a noose around his neck, as though preparing to hang himself. The video in question showed Jeffy don a noose and threaten suicide after his father, played by another doll, refused to buy him an iPad. A day later, Thirtyacre apologized.

After the noose incident, YouTube placed age-based restrictions on Thirtyacre?s channels, thereby disappearing his videos from the Kids app (but not necessarily restricted mode). Yet Thirtyacre?s history suggests that YouTube?s decision may be difficult to enforce: He can always create a new channel and hope he doesn?t get caught again.

So how did Thirtyacre gain millions of followers by publishing such crude content? One partial answer is children?s natural interest in subversive humor. H. told me his favorite character was Jeffy?s frequently irritable father, portrayed by a Super Mario doll. ?It was sort of, like, fun watching him being the bad parent,? he explained.

There is no doubt that many, and perhaps most, of Thirtyacre?s videos are gratuitously vulgar, to a degree that would astonish many parents. But as I continued to watch them, I became less certain that the videos? transgressive sensibility was the key to their appeal. Thirtyacre obviously traffics in racist tropes and taboo humor. He also clearly understands, on what seems to be an intuitive level, how to use storytelling and stagecraft to connect with and hold the attention of young children.

Thirtyacre has lived on YouTube for the past decade, spanning one of the most formative periods of a person?s life. His symbiotic relationship with the platform, intensified by what appears to be a tumultuous family life, is a central aspect of his persona. Some of his closest friends, including his girlfriend, have also amassed comparable audiences on YouTube. At the same time, YouTube presents a fertile environment for bigotry. So it cannot be entirely surprising that a young person who has breathed its air since seventh grade, while being paid gobs of money to do so, might absorb and recirculate some of the platform?s more insidious elements without pausing to weigh their meaning. Before Thirtyacre created Super Mario Logan, YouTube created Logan Thirtyacre.

S., Cook?s seven-year-old, stopped watching SML last year. ?I think it?s inappropriate, it?s sexist, it?s racist, and I would not recommend it,? he said. Nine-year-old H. agreed: ?It?s sexist and racist and said a lot of bad things about Asians.? Both credited their father?s intervention. ?Clearly that conversation, which was probably a year ago at this point, had an impact,? Cook said. H. even persuaded the same friend who introduced him to SML to stop watching too. Creators like Thirtyacre and platforms like YouTube may have less power than we realize. ?In fourth grade, everybody was like, ?Oh yeah, Little Jeffy, have you seen the videos??? H. recalled. ?Now it?s sort of like, ?Man, nobody really watches it anymore.??