This article deals with various mental health issues including depression and anxiety. It also contains spoilers for the video game ?The Beginning Game?. I would ask that you support the creator of The Beginning Game by playing through his video game first, or at least by watching some minutes of a playthrough to understand the style of his games before you begin reading.

Davey Wreden is an incredibly successful video game creator. His biggest hit, The Stanley Parable, is currently considered a cult classic, and is something that most serious indie gamers have played by now. But the point of this article isn?t to talk about the success of the game. Wreden admitted that, after the release of The Stanley Parable, his depression skyrocketed, and he had a hard time dealing with the world around him. In 2015, he released a new video game titled The Beginner?s Guide.

Main menu for ?The Beginner?s Guide? by Davey Wreden

Main menu for ?The Beginner?s Guide? by Davey Wreden

The Beginner?s Guide starts out as a sweet memento for his friend, who he calls Coda. Wreden narrates the game, explaining that Coda stopped making games in 2011, and Wreden wants him to continue. Wreden places the player into the very first game that Coda created, and begins talking about the metaphors hidden within the game. The landscape is a simple desert town, with crates and awnings to jump around on. However, Wreden points out that some of the crates are, in fact, colored blocks; they take the player out of the desert scene by reminding them that the realistic town around them is not real. Wreden explains that this was Coda?s first step into realizing what he wanted to do with his games; remind the player playing them that someone built the levels they play, and that there is a video game creator trying to connect with them in every game they go through.

After finishing his narration of the first game, Wreden quickly takes us into another game that Coda made. I won?t go through every single one that he created, because there?s a lot, but Wreden does make it clear that there are signs of depression and anxiety Coda exhibits through his games that are apparent in metaphors that Coda creates.

The first big metaphor that Wreden touches on in Coda?s games is a puzzle that Coda returns to in much of his work. In it, the player has to flip a switch to open a door, but once they go inside the door, there is a dark space before another door that will not open. Think of it like an unlit closet, with two doors facing each other; open one door and enter, but there is no way to open the other door from inside the closet. The solution to the puzzle is to open the first door using the lever, then click the lever again to close the door while entering the ?closet?. This way, the door will shut behind the player while they are stuck in the room. Once the door has closed all the way, another lever stuck to the back of the door is revealed, and the player can flick it to open the second door and complete the puzzle. Wreden shows many examples of Coda?s games that include the puzzle, and explains more about the metaphor, which we?ll touch on later on.

The outside of the infamous ?two-door puzzle? Coda designed

The outside of the infamous ?two-door puzzle? Coda designed

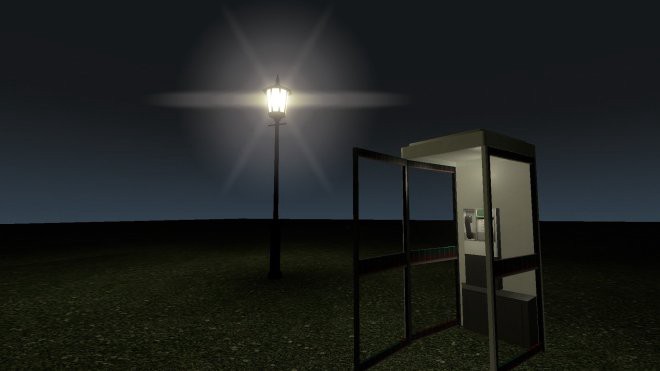

Another important metaphor is a lamppost that Coda places at the end of every single game, signifying the ending point of everything. Wreden loves the lampposts. He enjoys the fact that there is an end to each one of Coda?s games, and that all of Coda?s games connect themselves to each other. Wreden explains that it?s satisfying to be able to see each of Coda?s games with a solid, complete ending. You explore the map, walk around the game, complete objectives, and are left with the knowledge that, in reaching the lamppost, you have successfully completed the game. You have reached the end and can continue onto the next game.

A lamppost signifying the end of one of Coda?s prison games

A lamppost signifying the end of one of Coda?s prison games

Coda also includes other metaphors throughout his games. In one, he explains at the beginning of the game to the player that the game they are playing is an online game, and that there are notes strewn around the map that are left by other players. Wreden allows the player to walk through Coda?s game and read the notes left by various players. They range in length and style; some say things like ?hey how are you? and others talk about the game itself ?i can?t do this puzzle!? ?such a cool map? ?this room is lame?. After reading several notes, Wreden allows the player to take a look around the enormous map the game takes place in. Every inch of the map is covered in glowing notes. There must have been hundreds of them, some in spots that aren?t even on the map?s pathway. Wreden then reveals that Coda never released any of his games to the public. The game was never an online game at all. Coda wrote thousands of notes to himself. There were no other online players.

Just one of the thousands of notes written by Coda, pretending to be another online player

Just one of the thousands of notes written by Coda, pretending to be another online player

Here, we begin to see a trend. Coda talks more and more to himself throughout his games. He creates other NPCs ? non-player characters ? to sit about the map and speak to him. He becomes obsessed with a game Wreden refers to as ?the prison game?, where the player is stuck inside of a prison that there is no possible escape from. He creates tons and tons of different versions of the prison game, until the final one; the player reaches a telephone booth and communicates with their past self, explaining that they made it out of the prison and that everything will be okay. Here, the player?s ?past self? asks repeatedly if things will get better. Wreden explains that this is Coda?s cry for help. Still, no one is playing his games. Coda is writing NPCs as a form of connection. He is trying to reassure himself that everything will be okay.

Wreden then takes us to a game that he says had a majorly positive effect on Coda?s mental health. It is a game where the player gets to go into a house and converse with another NPC, who tells them about life and dealing with stress. The NPC is a housekeeper, and the player goes about the house and straightens the house, doing things like clearing the dishes, making the bed, fixing pillows, and other calming tasks. At the end of the cleaning cycle, it begins again; the player goes back and clears dishes that suddenly reappear, make a bed that has suddenly become messy again. The conversation with the NPC becomes deeper and more profound. The NPC offers life advice. There is calming music in the background. About halfway through the second cycle, the player is suddenly thrust out of the house, and the cleaning cycle ends. Wreden explains that he believes this game connects to the puzzle metaphor; the cleaning cycle and calming music are where Coda wants to remain, but he must continue on and out of the puzzle to complete the game. He believes that this philosophy ? the fact that there are safe places we can go, but, in the end, we must continue onwards ? had started applying to Coda?s life as well; not just his games.

The serene house and NPC with dishes to be cleared at the beginning of the cleaning cycle

The serene house and NPC with dishes to be cleared at the beginning of the cleaning cycle

Eventually, Wreden admits that he showed Coda?s games to other people that he trusted. He said that he felt good about showing them the games, that he felt proud of himself for showing off Coda?s work. He wanted Coda to realize that his games were amazing and that he should start publishing them and showing them to the world. He says that not only did the people who played Coda?s games enjoy them, they really wanted more. Coda?s games were successful and meant something to the people that tested them. Wreden, however, insinuates that, although he was proud of what he?d done for Coda, Coda did not feel the same way.

Wreden shows the player through more of Coda?s games, before placing us through last game Coda ever made in 2011. Wreden allows the player to try to complete the game. It is impossible to play. The game has no ending. Wreden uses his own code to open the final door of the game and show the player what is inside.

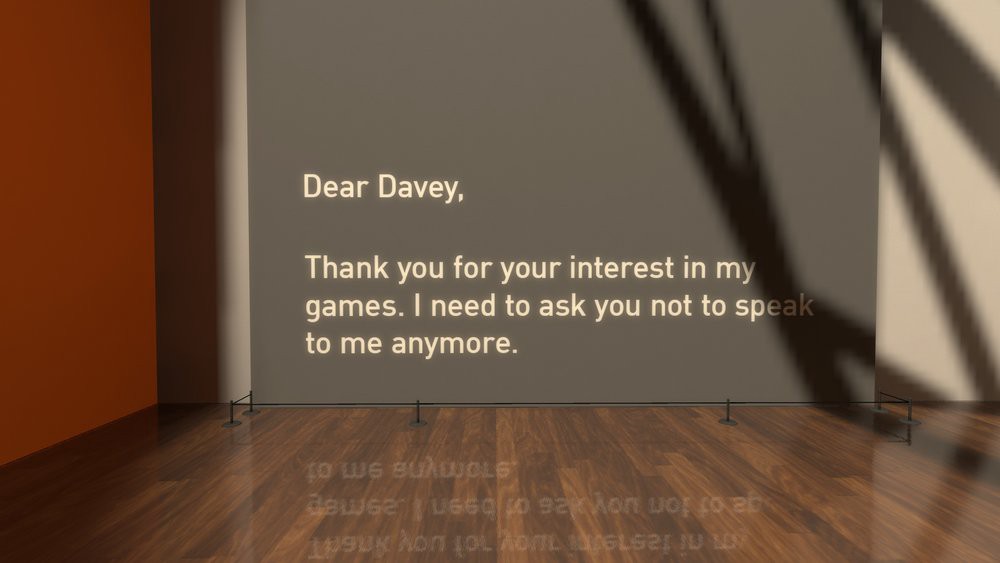

In the final room of the last game of Coda?s is a message. It is to Wreden. It explains that Coda does not want Wreden to contact him again. Coda goes on to say that Wreden has attempted to add meaning into his games. Coda asks that Wreden ?stop adding lampposts? to his games, implying that Wreden was the one who needed an ending to every game of Coda?s, and coded over them to make one for himself. Coda says that he is not depressed, and is not socially anxious. He tells Wreden that these are his own problems that he is projecting onto Coda. Coda explains that he has made some of his games for Wreden specifically, hoping that he will be able to see his own mental health issues and recognize that he needs help, but that Wreden showing others his games without permission was the final straw.

A portion of the final message from Coda to Davey Wreden

A portion of the final message from Coda to Davey Wreden

The message ends, and Wreden tells us that he has not heard from Coda since.

In a final moment of heartbreak, Wreden begs Coda to accept The Beginner?s Guide as an apology from Wreden. He hopes that displaying Coda?s games one last time will get his attention. He exclaims brokenly into the microphone that he is sorry for everything that he is done, and only wants to know how he can make it right.

That is the game?s ending.

Here is where things get interesting.

Coda does not exist. Coda never existed.

Wait, what?! Who was Wreden talking about? The game was not fictional; it was real. So, who is Coda? Wreden admitted on a podcast that the character of Coda is fictional. Some people choose to believe that Coda is a character based off of a coworker or other important person in Wreden?s life. But most choose to follow a different theory.

Some choose to believe that Wreden would never show someone?s games to others without their permission, particularly someone so close and dear to him. They believe that Coda represents Wreden?s depression.

I believe in this theory as well. It is shown that Coda speaks to himself in all of his games; he leaves notes for himself in his ?online? games and makes NPCs that tell him what he wants to hear. It is highly possible that Wreden has literally personified his depression, attempting to explain to players his attempts at success and moving past the struggles he?s faced in his life. Players have also pointed out that it would be illegal for Wreden to publish someone else?s work without their permission, so most speculate that the games must be Wreden?s. In which case, The Beginner?s Guide paints a much sadder story. At some point in his life, Wreden lost himself. He started placing metaphors into his games. He fuelled his depression into his work and relied on fictional characters to converse with him and explain that everything will be okay. Each metaphor that ?Coda? had placed into his games was, in fact, Wreden?s own cry for help.

Wreden has declined to comment on The Beginner?s Guide, other than to explain that Coda is fictional and does not exist. He leaves the game up to interpretation. However, he has been open on social media about his own depression and life problems, particularly after the successful release of The Stanley Parable.

The Beginner?s Guide was heartbreaking to players of the game. People related to the struggles of Davey and Coda, and some even related to the personification of depression, the idea of drawing into yourself and struggling to explain your problems to others. It is difficult to play through; the heartbreak in Wreden?s own voice as he asks for Coda to come back and release more games. Is this Wreden?s way of begging himself to come back from depression and continue with his life? Is it a plea to the audience to fall back onto other people for help, rather than their work? Is it a way of apology from Wreden to himself; is he using the game to explain his struggles and depression, and hope that other people can relate and recognize the problems within themselves?

Although Wreden?s story may not be relatable to others in each of its terms ? most of us are not video game developers, for example ? it is relatable in certain ways. We can recognize each of the metaphors ?Coda? uses in his games. The puzzle ? the wish to stay in a safe place before moving onto the next chapter of our lives. The lamppost ? an end to each game, an end to every segment and trauma that we experience. The prison ? the impossible-to-escape seclusion, the hope that we can see ourselves escaping from misery and solitude and moving on with our lives. Wreden has created something meaningful and personable. He has shown us the things that he struggles with, and we can see ourselves in them. That, in itself, is truly the most heart-wrenching realization of the game; Wreden can project himself onto Coda, personifying his depression and explaining more easily the struggles of his life. But we ? as players, watchers, readers ? can project ourselves onto both Wreden and Coda; we struggle with and fail to recognize our issues, cutting ourselves off from self-love and self-acceptance, trying to find lampposts that don?t exist.