Bob Dylan: Harry McClintock [was] an actor, poet, and painter? and a songwriter. He wrote a song called The Big Rock Candy Mountain from the perspective of a hobo. He gained experience from traveling all over the land with the unemployed. He had great respect for the hobos and bums and became their musical voice. The song Big Rock Candy Mountain is about a heaven for the homeless. The dogs have rubber teeth. The police have wooden legs. The jail bars are made of tin. They?re going to ?hang the jerk who thought of work.? Well, it?s got a catchy tune, and kids loved it, but these weren?t appropriate words for kids. So, they changed it. The cigarette trees became the peppermint trees that you remember. The streams of alcohol ? that?s right ? they became the streams of lemonade. And that lake of soda pop you asked about is really a lake of whiskey. People like Burl Ives recorded the kid?s version, and it?s great for kids to learn songs like this, but here on Theme Time Radio Hour we?re all grown-ups. So why don?t we listen to the original version of Big Rock Candy Mountain by Harry McClintock. ~ Phone call during the ?Sugar & Candy? episode of Bob Dylan?s Theme Time Radio Hour, airdate: February 25, 2009

Harry McClintock aka ?Haywire Mac

Harry McClintock aka ?Haywire Mac

Harry McClintock, known at various times in his colorful career as ?Haywire Mac,? ?Radio Mac,? sometimes simply as ?Mac,? and maybe once as ?Hats McKay,? (more on that one later) was born on October 8, 1882 in Knoxville, Tennessee.

When he was fourteen Mac ran away from home to join the Gentry Brothers Dog and Pony Show. In addition to serving in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, Mac worked on the railroad, as a cowboy, stevedore, and as a union organizer with the ?Wobblies? (Industrial Workers of the World). He claimed to have written Big Rock Candy Mountain ? originally titled as The Big Rock Candy Mountains ? sometime around 1898 when he was 16 years old, on the bum, and singing for his supper on New Orleans street corners. ?But my new trade,? McClintock told an interviewer, ?brought new dangers. I was a shining mark; a kid who could not only beg handouts but who could bring in money? a valuable piece of property for the jocker who could snare him? there were times when I fought like a wildcat or ran like a deer to preserve my independence and virginity??

That last word, virginity, is key. McClintock is referring to one of the dirty little secrets of the Romance of the Open Road. Rather than yard bulls and train wheels, the biggest danger a youth on his own faced was being besieged by predatory hobos, known as ?wolves? and ?jockers,? who promised food, protection, booze, and what-all in exchange for the boy?s, ah, sexual favors.

Ghost Stories

?The Big Rock Candy Mountains may appear a nonsense song,? noted a commentary that accompanied the first publication of the adult version of the song. ?But to all pied pipers in on the know it is an amusing exaggeration of the ?ghost stories? used in recruiting kids.?

?Ghost story? was a hobo slang term for any plausible ? but untrue ? story, whether told to a housewife in order to promote a handout, or told to a young boy to entice him into the hobo life. As ghost stories go, The Big Rock Candy Mountains was one big fable of fun and adventure, where cigarette trees, lemonade springs and soda water fountains were always at hand for the taking. Harry McClintock?s claimed original is pretty much recognizable as the better-known Big Rock Candy Mountain, at least up to the final stanza, where a sadder but wiser lad tells his older traveling companion:

The punk rolled up his big blue eyes And said to the jocker, ?Sandy, I?ve hiked and hiked and wandered too, But I ain?t seen any candy. I?ve hiked and hiked till my feet are sore I?ll be God damned if I hike any more [To be buggered sore like a hobo?s whore] In the Big Rock Candy Mountains.?

The exact wording of that penultimate line is in question, as both published transcripts of The Big Rock Candy Mountains blank the line out to spare the tender sensibilities of their readership. Musicologists have extrapolated gentler versions of that missing line, and some have come up with even more randy versions. But in all cases, the ah, thrust, is the same.

For obvious reasons, Harry McClintock never recorded his ?adult? The Big Rock Candy Mountains, although he came teasingly close in a 1953 interview. He did record a clean version for Victor in 19 and 28, copyrighted the song in December 1928, and promptly launched a plagiarism suit against a ?Billy Mack,? a ukulele player who had copyrighted the sheet music for his take on Big Rock Candy Mountain that same year. McClintock produced his lyrics, including the final stanza featuring the buggered boy, as evidence of his authorship to what must have been a very bemused judge.

Some writers have noted that the court ruled that Big Rock Candy Mountain was a traditional tune and in the public domain, fair game for any musician to try his hand at. But it appears that McClintock did prevail in his suit.

While a ?kid?s version,? as Bob Dylan called it, of the song is copyrighted by Burl Ives, and several other versions are in the public domain, McClintock?s heirs do definitely own the copyright to Harry McClintock?s version of The Big Rock Candy Mountain and are not shy about defending their rights to that composition.

In 2005, those heirs obtained settlement from fast food flinger Burger King for its unauthorized use of the song?s melody in a 2005 commercial. According to paperwork filed by McClintock?s estate for that suit, his version of Big Rock Candy Mountain was originally copyrighted in December of 1928, the year of McClintock?s suit against Billy Mack, and the copyright is still in force. According to current U.S. copyright law, McClintock?s song won?t enter the public domain until 2023.

The Candy & Bum War ? The Twisty History of Big Rock Candy Mountain

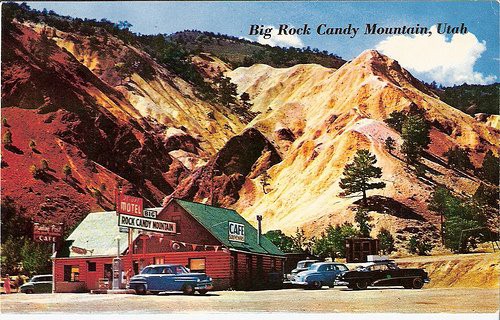

Big Rock Candy Mountain, Utah

Big Rock Candy Mountain, Utah

Copyrights aside, it?s likely that Harry McClintock?s version of Big Rock Candy Mountain was one in a long line of songs and children?s rhymes derived from an English ballad that first appeared in written form in 1685, called An Invitation to Lubberland. In Lubberland, all the brooks and streams ran with fine wine, and the hills were spun of sugar candy.

And the many versions of Big Rock Candy Mountain(s), including Harry McClintock?s, are themselves variations of another, even more explicit song called The Appleknocker?s Lament, a copy of which was sent to folklorist Robert Gordon in 1927, and which is believed to be have been written circa 1900. Outside of McClintock?s claim, The Appleknocker?s Lament is the only known example of an adult Big Rock Candy Mountain. Possibly it was written by McClintock as an early version of his better-known song.

Tellingly, the Big Rock Candy Mountains themselves make an appearance in The Appleknocker?s Lament, as does a disillusioned kid, who relates very explicitly that he?s tired of sitting on a hobo?s peg and of being a ?punkerino.?

Yet another The Big Rock Candy Mountains was published in 1906 by the songwriting team of Marshall Locke and Charles Tyner ? some 22 years before McClintock recorded and copyrighted his version. While Locke and Tyner?s lyrics appear to be derived from the The Appleknocker?s Lament, their G-rated protagonist only suffers the fate of having his clothes and shoes stolen by the bum who enticed him to take to the open road.

You would think that Locke and Tyner?s 1906 published sheet music would have put paid to McClintock?s 1928 lawsuit about who owned The Big Rock Candy Mountains ? unless he was also the unknown author of The Appleknocker?s Lament.

However, Harry McClintock had moved into radio in a big way in the mid-1920s, becoming ?Radio Mac? by the time of his 1928 lawsuit. Remembering that he had sold post cards dated 1905 with the bowdlerized version of the song?s lyrics, Radio Mac put out a on-air call to his audience asking if anyone still had one of those cards. As it turned out, several of his listeners did, and sent not only cards with the lyrics to Big Rock Candy Mountain, but also cards with the lyrics to Hallelujah, I?m a Bum, another song that Mac claimed to have written and then saw purloined.

Even though he eventually was awarded copyrights to both songs, McClintock complained bitterly about their appropriation in a letter to the League of Composers, asking how they thought so-called ?hillbilly? songs could apparently be written by no one.

?The theory seems to be they are created by some sort of spontaneous generation,? he wrote.

McClintock claimed he had authored Hallelujah, I?m a Bum at around the same time he wrote The Big Rock Candy Mountains, taking the music from the hymn ?Revive Us Again,? and originally titling it, Hallelulia on the Bum.

John Greenway, who first collected the randy version of McClintock?s The Big Rock Candy Mountains for his book, American Songs of Protest, was willing to give Mac the benefit of the doubt, although he did note that McClintock offered virtually the same evidence for his claims to both songs. That is, Mac produced a version of each song with some added and some changed lyrics and claimed those lyrics as the true originals.

Miss Peggy Lee, Mr. ?Hats? McKay, and the Battle of ?Maana? In 1947, singer/songwriter Peggy Lee had a hit with a song she had co-authored, Maana. One ?Hats? McKay, described in newspaper reports as an ?elderly banjo player,? filed a plagiarism suit against Lee and company, claiming that Maana was a reworking of a song ?Hats? had written way back in 19 and 19, Midnight on the Ocean.

According to Lee?s biography, Fever: The Life and Music of Miss Peggy Lee, ?Hats? McKay real name was ?Harry McClintock.? However, Lee?s biographer, Peter Richmond, confused vaudevillian Walter C. ?Hats? McKay with our Haywire Mac, and conflated their different lawsuits over the ill-starred Maana.

In Richmond?s defense, the Maana lawsuits are easy to confuse. Our Harry McClintock was the author of a song he had copyrighted and recorded in 1928 ? the year a busy one for Mac ? called Ain?t We Crazy. The song?s melody, and the source for some of its lyrics, was from a traditional tune called ? you guessed it ? Midnight on the Ocean.

McClintock?s publisher, Sterling Sherwin, who had something of a career copywriting public domain music, took the step of publishing Midnight on the Ocean in 1932 under his and Mac?s names with a slightly changed title, It?s Midnight on the Ocean, and in typical Harry McClintock fashion, with some changed and some added lyrics.

Sherwin and Mac did sue Lee, claiming Maana?s melody was copied from It?s Midnight on the Ocean. But their sleight-of-hand didn?t work, and the judge ruled that whether copied or not, whether copyrighted or not, the shared similarities of the melodies were both derived from the public domain Midnight on the Ocean.

Sherwin and Mac dropped their suit, but Maana had to face two more suits over its legitimacy, including the one brought by ?Hats? McKay. Rather than Midnight on the Ocean, McKay claimed that Maana?s melody was a copy of his The Laughing Song, which he claimed to have written in 1919 and popularized in his vaudeville act.

Lee?s attorneys presented various defenses, that McKay hadn?t written The Laughing Song; that even he had, he had never properly copyrighted the song; and that ?Hat?s? hand-written manuscripts proving his authorship looked suspiciously new. Even if he had written The Laughing Song, Maana was a samba, a musical form which Lee?s lawyers claimed didn?t exist when McKay had written the melody of The Laughing Song. Q.E.D. Maana and The Laughing Song couldn?t share any musical DNA.

In any case, the lawyers argued, ol? ?Hats? had barely performed in the past 20 years, and his The Laughing Song had seldom been heard off the vaudeville stage. There was no sheet music, no recording of the song. So, where would Peggy Lee have found it?

?Hats? McKay lost his case against Peggy Lee. This may have been partially due to his habit of strumming his banjo while court was in session, irritating the judge no end. More likely the scales of justice tilted in Peggy?s favor when her friend, singer, pianist, comedian, actor, Jimmy Durante, made a surprise court appearance, wheeling in a piano and launching into a melody of tunes, all of which shared musical similarities with Manana.

With the Ol? Schnozolla on your side, how could you lose? The court ruled in Lee?s favor. ?Hats? retired back into the mists of history. Manana, however, wouldn?t be a particularly happy memory for Peggy Lee. Her co-author husband, who had a drinking problem, went out on a binge to celebrate their winning the case, and tried to sell the rights to the song for two tickets to the Rose Bowl that same night.

A Poet, Pirate, Pauper, Pawn and a King

As well as becoming ?Radio Mac? Harry McClintock hosted a popular children?s radio show in San Francisco called ?Mac and his Gang.? He?d later try his hand in Hollywood and made appearances in several Gene Autry films, although his part was usually limited to saying ?He want that-away.?

In the early `50s, Mac returned to San Francisco and radio, and eventually even television. He passed away at age 74. He was at various times in his life a bum, street musician, cowboy, railroad brakeman, poet, painter, actor, labor organizer, magazine writer, and model for several fictional characters? ? and maybe the composer of Big Rock Candy Mountain and Hallelujah, I?m a Bum? maybe even The Appleknocker?s Lament. ?or maybe not.

Have a comment or question? Email me at [email protected]

Like this article? You might also like:

?Murder! he says: The Spade Cooley Story

Oh Mercy: Bob Dylan, Chronicles, and the Mysterious Hand Injury

Bob Dylan & the Strange Journey of Warhol?s Silver Elvis

Dylan, Newport `65 & the Search for the Green Polka-Dot Shirt

All the Lies That Are My Life: Bob Dylan, Lorre Wyatt and ?Blowin? in the Wind?

Crawling from the Wreckage: Bob Dylan and his Motorpsycho Nitemare

Bob Dylan, Knocked Out Loaded, and the Daughters of Doom

Real Life or Something Like It: Bob Dylan and the Asia Series